Neon Genesis Evangelion's Apocalyptic Psychology

Evangelion Unit-01 after surviving an enemy angel’s attack. Still from Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995, dir. Hideaki Anno), Gainax/Project EVA, licensed by Netflix.

The word “apocalypse” is Greek for “revelation”, an unveiling of secrets that could never be known without divine intervention. Our current apocalyptic moment, driven not by any supernatural force but by viral RNA, protein spikes, and respiratory droplets, doesn’t reveal any divine plan but rather strips away the veil that had previously concealed the vast systemic dysfunctions of global society from direct view. Simultaneously, this crisis could be a revelation about each of us: how we try to live while staring down what often feels like an inevitable, fated end.

If you can tear yourself away from Tiger King, Netflix has a series that deals with this theme: people trying to live during the end of the world. Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995, dir. Hideaki Anno) presents itself as a giant robot anime, but action loses its centrality as the series progresses. Minus the tropes of the genre, Evangelion presents a story of how dysfunctional individuals try (and fail) to live their lives while facing a mounting unavoidable catastrophe.

The Second Impact as seen from space. Still from Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995, dir. Hideaki Anno). Gainax/Project EVA, licensed by Netflix.

Evangelion takes place after civilization collapsed following an event called the “Second Impact”. Half of humanity was wiped out by climate change, nuclear war, and disease after the catastrophic awakening of supernatural beings called “angels”. Fifteen years after, these angels have returned, but thanks to the secret military organization NERV humanity is able to fight them using the titular giant mecha. The angels need to be defeated or else they will trigger the “Third Impact”, humanity’s ultimate end.

The Third Impact as seen from space. Still from End of Evangelion (1997, dir. Hideaki Anno), Gainax/Production I.G., licensed by Netflix.

Towards the series finale, it is revealed that the Third Impact will occur no matter what anyone does. The end cannot be prevented or postponed. All there is to do is wait, counting down the time that’s left. But how does one live in this situation, every moment infused with suffocating apocalyptic meaning? The main characters of Evangelion cope in a variety of ways. Shinji Ikari, manipulated by his father into becoming an Evangelion pilot, is the main protagonist. From the very first episode, his response to any “fight or flight” situation is the latter.

Shinji running away from NERV. Still from Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995, dir. Hideaki Anno). Gainax/Project EVA, licensed by Netflix.

Rei Ayanami is also a pilot, but her attitude stands opposite of Shinji’s—she never disobeys orders or backs away from a dangerous situation. She exemplifies extreme selflessness: if you have nothing to lose, what’s the worst the end of the world can do to you?

Rei, setting her Evangelion to self-destruct in a desperate attempt to kill an angel. Still from Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995, dir. Hideaki Anno). Gainax/Project EVA, licensed by Netflix.

Asuka Langley Soryu is the third pilot, and her approach is one of relentless perfectionism. She constantly needs to prove that she is the best at everything, and her entire identity revolves around being the top Evangelion pilot. Her response to any situation is to fight against it as hard as she can.

Asuka, fighting a losing battle against ten enemies at once. Still from End of Evangelion (1997, dir. Hideaki Anno), Gainax/Production I.G., licensed by Netflix.

What makes the psychology of Evangelion’s characters compelling is that nobody is well-adjusted or normal. Everyone has some pathology or dysfunction, and as the situation becomes increasingly desperate, everyone cracks from the pressure. There is no such thing as a “normal” reaction to trauma in real life, either. Evangelion is full of references to psychoanalytic theory, and one lesson it can teach us is that psychopathology is not exceptional. Rather, it’s the default human condition, rising from a rift in our subjectivity. We are driven by the impossible desire to fill this lack; if there is anything that passes for normal, it is this wounded incompleteness. And, in our futile attempts to become whole, we—like the characters in Evangelion—end up hurting each other.

Shinji, in Unit-01, deciding whether the final angel lives or dies. This shot lasts for over a minute. Still from Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995, dir. Hideaki Anno). Gainax/Project EVA, licensed by Netflix.

Evangelion isn’t a treatise of how one ought to live in a hopeless situation: nobody should model their behavior on how these characters act, but the truth is that many of us behave similarly. In Evangelion, as in our world, human beings are unequipped to live under the shadow of doom. This psychological realism is a mirror in times like ours, reflecting our perceived faults and inadequacies back at us and offering reassurance that it’s normal to not feel normal. If there is any comfort to be found in the apocalypse, it is that everyone is going through the same thing. Our individual traumas are unique and may be difficult for others to comprehend, but now we are united by a lack of control over our lives: we’re all alone together.

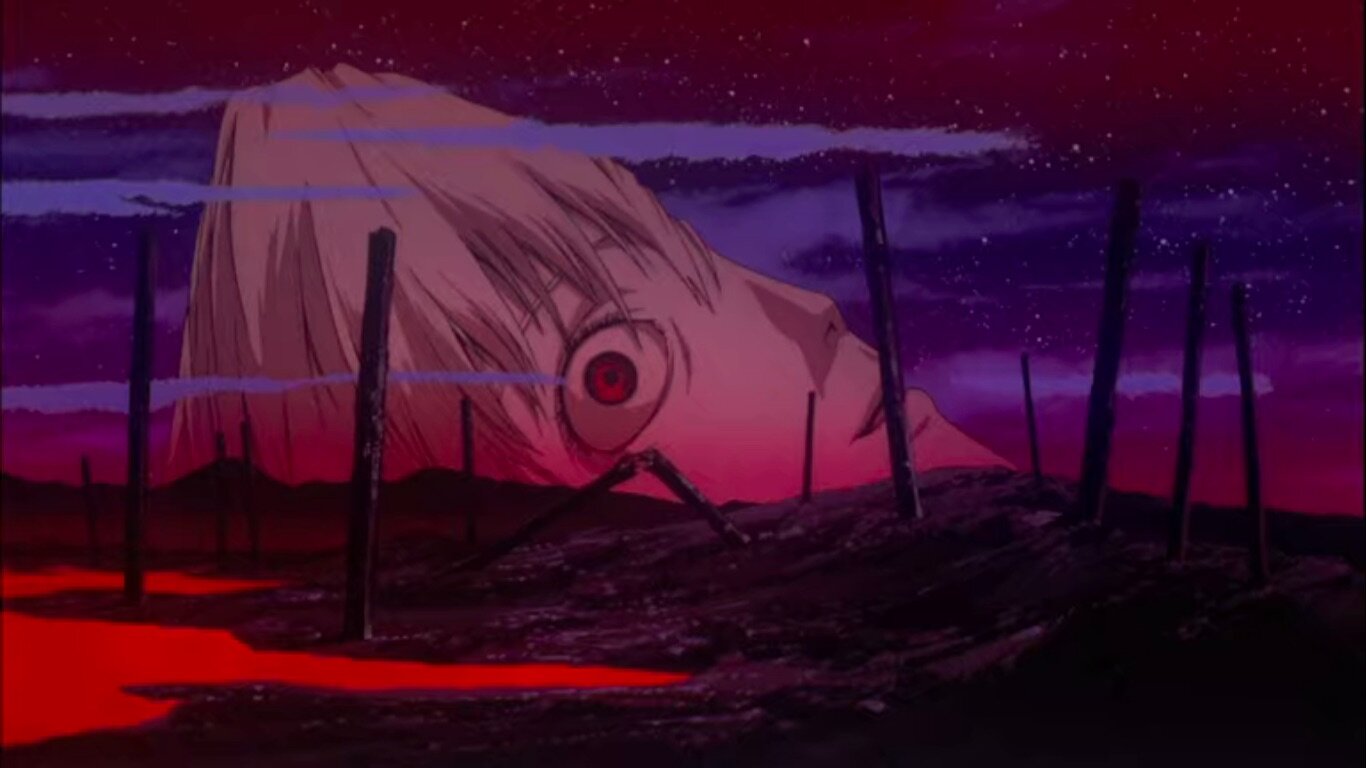

Aftermath of the Third Impact. Still from End of Evangelion (1997, dir. Hideaki Anno), Gainax/Production I.G., licensed by Netflix.