Route to [re] settlement

On Sunday May 1st, Historic Columbia’s Mann-Simons site opened its doors to a function that has indirectly been in the making since the transfer of ownership of the property in the 1970s. The Mann-Simons site was transformed into an art exhibition space that explored African American life, history, and culture entitled, Route to (re) settlement. Attendees including myself were met with the summer’s thunderstorms that poured rain from the house museum’s gutters onto two beautifully crafted quilts created by artist Victoria Idongesit-Udondian and several women from the neighboring Marion Street high-rise. Unbeknownst to many, Victoria and others prepared these quilts for the inclement weather to come, an effort that subtly speaks to the overall history of the Mann-Simons site, the family, and community members who stood as stewards of this property for well over 150 years.

The Mann-Simons site was home to free blacks, Ben Delaine and Celia Mann, originally from Charleston South Carolina, beginning around 1843 with the purchase of a plot of land situated on the corner of Richland and Marion Street in downtown Columbia South Carolina. Their occupation of this area included a main house at 1403 Richland Street, a ‘lunch room’ at 1401 Richland Street, a grocery at 1407 Richland Street, a small three-room structure at 1407 Richland Street, and a smaller house that was situated directly behind the main house at 1904 Marion Street. Agnes Jackson inherited these various lots from her mother Celia Mann upon Celia’s death in 1867. Agnes Jackson had a total of eight children from husbands William Simons and Thomas Jackson, who all aided in managing the estate. Between 1891 and 1903, the Columbia City Directory listed John L. Simons, son of Agnes Jackson, as the owner of the ‘lunch room’ at 1401 Richland Street. John L. Simons lived next door to his business at the 1904 Marion Street house. The grocery store at 1407 Richland Street was ran by John L. Simons in 1904 and then by his younger brother Charles H. Simons by 1906 (Columbia City Directory). The main house included four rooms, an attic and basement in which became the residence of thirteen people, including an African American servant by 1900 (12th Federal Census). In 1970, through eminent domain, the Columbia Housing Authority acquired the site, leading to a grassroots preservation movement that saved the main house, which opened as a museum in 1978.

Through several generations of family who lived on this property one realizes as Kimberly Light (curator) puts it, “…the grounds encapsulated the historical and current socio-political and cultural climate in the United States and beyond. The Mann Simons family became leaders transforming the corner of Richland and Marion Streets into one hub of the black community throughout the eras of Reconstruction, Jim Crow segregation, the Civil Rights Movement, and now reactivated by contemporary artists. The prominence of this site within the community is underscored by the archaeological artifacts uncovered by Dr. Jakob Crockett and Joseph Johnson, which offer a framework into the daily lives, occupations, and recreational past-times of the family and the community in which they lived. “It could be suggested that by this family serving as a beacon throughout their occupation of the property, the community felt impelled to take a leadership role in saving the house from demolition, thus saving the legacy and architectural footprint of the Mann-Simons family. This footprint is celebrated yearly by Historic Columbia during its annual Jubilee Festival of Heritage.

As I watched visitors converse while enjoying the artistic works of Henry Taylor, Fletcher Williams, III, Rashid Johnson, Michi Meko, and Victoria Idongesit-Udondian, I suddenly realized that the vision of the black community who advocated saving the Mann-Simons Site from imminent domain had come to fruition. Community members like Modjeska Simkins, family relative Robbie Atkinson, Luther Battiste, and Congressman James E. Clyburn all knew that this site served as more to the community than solely a house museum. It was a hub for African American cultural ideas to be explored and exchanged in the efforts to carry on the legacy of the family in which inhabited the property. C.C. Buyers, the only person to serve as curator for the Mann-Simons Site, spoke of a community vision that wanted to save the house for the purpose of it being a site where organizations could gather to hold private and public functions exploring black art, history, folklore, and culture.

The original vision of the black community was subtly reengaged by curators Kimberly Light (Connelly & Light) and Cecelia Stucker, director (CC: Curating & Collections), who both drew inspiration from their visit to Historic Columbia’s Mann-Simons Site. Light and Stucker were interested in how the complexity of the Mann-Simons Site’s heritage could be explored and interpreted from an artist’s perspective.

Henry Taylor

Victoria bla bla, Many makes One,

2016

Acrylic on canvas

12 x 12 inches

Henry Taylor

Came in a plane, but the same, drowning Blues

2016

Acrylic on canvas, matte medium, house paint on wood, vinyl, found antique ship

Henry Taylor

SPELL

2016

Inspired by his first visit to South Carolina, Henry Taylor, a Los Angeles artist, incorporated objects and peoples he encountered in and around the Mann-Simons Site into assemblage-paintings that activate the historical tapestry of the house, grounds, and community. Oriented in his practice of culling from family, friends, and historical and popular culture figures, Taylor captures idiosyncratic portraits of the socio-political landscape and figures that occupy contemporary society. Taylor’s vibrant and spontaneous style conjures rhythms similar to the acoustic equivalent in blues and jazz, while his subjects’ composition evokes critical social acumen described within the lyrical genius of artists such as Nina Simone and N.W.A. Taylor’s portraits of fellow artist Victoria Idongesit-Udonion and Palmetto Curatorial Exchange Intern Isaac Udogwu, both Nigerian-born, are positioned among an array of altered-objects that simultaneously reference the history of enslaved African Americans brought from the West Coast of Africa to the port of Charleston, popular African American culture and objects inherent to the family room of a domestic setting such as that found in the Mann-Simons Cottage.

Fletcher Williams, III

Boosie 3:19

2015

Poplar pine, handmade palmetto roses, laser-cut plexi

24 x 20 x 3 inches

Fletcher Williams, III

2015

Poplar pine, handmade palmetto roses, laser-cut plexi

24 x 20 x 3 inches

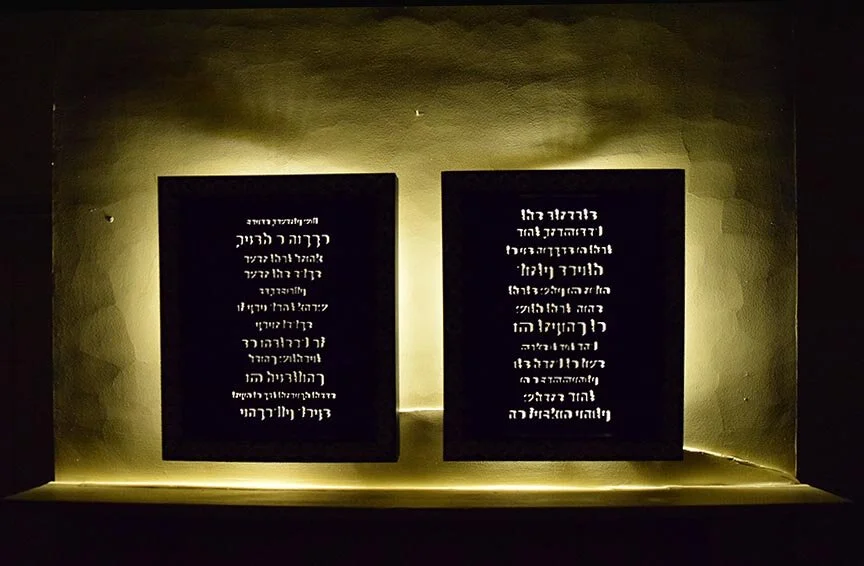

Charleston-based artist Fletcher Williams, III, created Souvenir in reaction to the 2015 Mother Emmanuel Massacre in which nine congregation members were murdered during their weekly bible study at Emmanuel African Methodist Church in Charleston. The objects within this series memorialize the victims of the massacre as well as the reconditioning of African American communities throughout the Lowcountry. Realities of racially motivated violence and social destruction starkly contrast with the Palmetto Roses framing his light boxes. This local souvenir – traditionally given to Civil War soldiers by their girlfriends and wives to bring them luck in battle – are woven by the artist using the techniques of low-income African American boys selling them as souvenirs in downtown Charleston. These floral works function as objects of beauty and indicators of violence for African Americans of the South Carolina Lowcountry. Juxtaposing them alongside the ambiguous scripture of the light boxes emits a shrine-like sense to the installation. Williams presents a selection of lyrics from songs by rappers Bun B and Boosie Badazz in “Quad Black” – a font he developed with an Islamic student he met while attending Cooper Union. The text is centered within the frame, recalling Hebrew scripture. Detailing the struggle of black adolescents and adults and their coping mechanisms with racial profiling, violence and discrimination, the two light boxes demonstrate the difficulties that blacks, like the freed slaves that settled the Mann-Simons Site, experienced from slavery through Emancipation and the residual trials prevalent in contemporary society. The spiritual references and abstracted sociopolitical commentary lend the works a contemplative feeling.

Rashid Johnson

Planet

Mirrored tile, black soap, wax, shea butter, vinyl

73 x 93 x 14 inches (185.4 x 236.2 x 36.6 cm)

Michi Meko

Black Leakage: Cast Buckets

2016

Galvanized steel, gold leaf

30 x 10 x 10 inches (each)

Michi Meko

Stinger

2016

Roasting pan, afghan, hornets nests, rhinestones, epoxy

48 x 12 inches

Michi Meko

Hearth Magic

2016

Red clay and burlap

6 x 6 inches

Drawing from his Southern familial history, and from traditional storytelling by way of culinary customs of his youth in rural Alabama, Atlanta-based artist Michi Meko endows banal discarded objects weighted with historical significance and spiritual powers. Reworking domestic objects from his family history, such as cookware, Meko creates poignant narratives emphasizing the buoyancy of black culture despite continuous oppression — be it flagrant or clandestine. For Meko, establishing a new metaphysical identity for these objects is a proclamation of remembrance and a nod to the archaeological excavation of the Mann-Simons Site, which offered a framework for historians and anthropologists to envision what the daily lives of the Mann and Simons family may have been like and contextualize their story for a contemporary audience. Interpreting the artifacts and defining the various structures of the site, reveals the struggles and the vibrancy of the families that lived here and the community to which they belonged.

Victoria-Idongesit Udondian

Code, (I) and (II)

2016

Muslin, secondhand clothing, under-under, thread, waterbased polyurethane, mixed media

280 x 35 inches

Victoria-Idongesit Udondian

Code, (IV)

2016

Muslin, secondhand clothing, under-under, thread, waterbased polyurethane

Dimensions, 67 x 36 inches

Through her focus on textiles and the capacity of clothing to shape individual and collective identity, Nigerian-born, New York-based artist Victoria-Idongesit Udondian uses her training as a tailor and fashion designer to inform her practice as a visual artist. Udondion’s interactive, sculptural performance confronts notions of authenticity and cultural contamination, particularly as techniques, patterns, and styles oscillate across borders and blur cultural references. Working with Charleston-based quilter Marlene O’Bryant- Seabrook, she constructed a community quilt with a group of women living in senior housing adjacent to the Mann-Simons Site. Udondion collaborated with the community by weaving several quilts and her own textiles from clothing sourced at His House Ministries, a local second-hand store with a religious affiliation that provides affordable clothing to members of the neighborhood. Pulling from donated denim and cotton textiles, the community-produced quilt is an extension of Udondion’s quilt, which is hung in the window overlooking the intersection of Richland and Marion streets. The community quilt winds onto the front porch, intertwines with the picket fences lining the front of the property, and echoes the indoor window quilt within the ghost structure that delineates the former shoe shop and store along the east side of the property. The patterns, techniques and modes of display are inspired by the historical mythology of quilts and the traditional and contemporary quilting methods of Lowcountry textiles.

Route to (re) settlement continues at the Mann-Simons Site, 1403 Richland Street, Columbia, SC through July 29.

Joseph Micah Johnson is an Urban Archaeologist and serves as the Our Story Matters Coordinator for the Columbia SC 63 initiative researching and documenting South Carolina’s capital’s role in the Civil Rights Movement. He has coordinated several events for the initiative like the “honoring of Revered C.J. Whitaker by Naming Historic Corner” and the “honoring of Civil Rights pioneers Frank Washington, George Elmore, Luther Battiste, and Anthony and Alice Hurley.” Prior to entering this position, he served as an Archaeologist for the Columbia Archeology Program. Johnson currently serves on Historic Columbia’s Jubilee Festival of Heritage committee, the Mann-Simons Scholarship Committee, and the Annual Statewide Karuma Black History Festival and Parade committee. Johnson is also an aspiring cinematographer and producer in which he uses this passion to explore African American history and culture. Johnson is native of Sumter, South Carolina, graduating from Sumter High School before attending the University of South Carolina. He holds a distinguished degree in Anthropology.